Armin and his father granted asylum in Hungary

‘God bless Hungary! I love Hungary and Hungarians. I have been waiting for this for two years and eight months. Thank you very much for accepting me and for granting me refugee status,’ said the sincerely shaken Abouzar Soltani on 18 August in the notes on his hearing when it was announced that he and his 12-year-old son Armin had finally received protection in Hungary. What follows is the story of what the Iranian clients of the Hungarian Helsinki Committee experienced, and the face that the Hungarian State shows to the persecuted.

The 988 day, often seemingly hopeless, tortuous process was full of lows; but it ended on a high. This was not just thanks to the goodness of the persecuted father, who had hitherto endured the tribulations with dignity. The authority, which had previously bared its teeth so many times, has now acted fairly and did not wait for the court to declare the Iranian man and his son refugees: the National Directorate-General for Aliens Policing (OIF) itself declared this. This way the case, which was clearly an embarrassment to the government, ended at least half a year earlier than expected.

Abouzar and his son Armin’s story is exceptional. Yet, it provides many general lessons about how Hungary’s asylum system functions, and to what extent the right to asylum, as included in the Fundamental Law of Hungary is enforced.

They were persecuted because of their Christian faith

Our client had a good job in Iran working in PR for a healthcare provider and as a decorator. Only so much can be said publicly about his escape, but the crux is that he thought of the world differently than the prevailing perception in Iran and was harassed for it. So in 2016 he decided to leave his homeland with his son. He wanted to live in a place where there was no need to be afraid if someone had a different opinion. He wanted to live in a place where freedoms are guaranteed, especially freedom of conscience and religion.

He was already acquainted with Christianity in Iran, and he officially converted to the Christian faith during his escape. He was baptized, and has been actively studying and working for years to spread the faith of Jesus.

They first reached Bulgaria, where Abouzar was locked up with his son for 42 days. Then they went to Serbia where they waited for two and a half years for a permit to enter Hungary and apply for asylum. This could not be done in Serbia, as Serbia sent them to Hungary with their asylum application. So, they legally came to Hungary in all respects.

On 5 December 2018, they passed through the gates of the container camp in the Röszke transit zone. They were then detained there for 553 days – until the transit zones were closed by the government; in part following an EU court ruling in their case. But their ordeal was still far from over…

Rejected by the Hungarian authorities

Because they arrived via Serbia, which was deemed ‘safe’, their asylum application was not examined by the Hungarian authorities 32 months before. Therefore, the Hungarian authorities said that their asylum application had to be processed by the Serbian authorities. They were expelled to Serbia in February 2019. There is no better indication of how ‘safe’ Serbia was for them than the fact that the Serbian authorities refused to take them back – just as no one else considered a ‘distant foreigner’ had been accepted since 2015.

However, the Hungarian authorities were still unwilling to deal with the father and son’s asylum application on the merits. Instead, a new expulsion destination was designated: Iran. This was precisely the country from which they had to flee, and to which they cannot return because they could even face execution because of Abouzar’s increasingly open Christian faith. In addition to their asylum proceedings, the Soltanis also filed three lawsuits against the Hungarian authorities. They were represented in these cases by Barbara Pohárnok, an attorney at the Hungarian Helsinki Committee.

The authorities arbitrarily did not consider them asylum-seekers, so they applied much stricter immigration rules to them. As a result, they were placed in an even worse sector of the transit zone from which they constantly feared deportation back to Iran. In addition, Abouzar also became one of those people who were starved in the transit zone. In March 2019, he received no food for three days and could only share his child’s ration. He only received food again after the Hungarian Helsinki Committee appealed to the European Court of Human Rights to immediately intervene in favour of Abouzar, and thankfully that happened.

Inhuman and degrading treatment

The father and son’s situation did not seem to change for a long time. Following a domestic court decision, there was a moment when they thought that they could escape from the container prison guarded by gunmen and dogs and surrounded by soul-destroying barbed wire fences, a place completely unsuitable for the long-term accommodation of children; but nothing came of it.

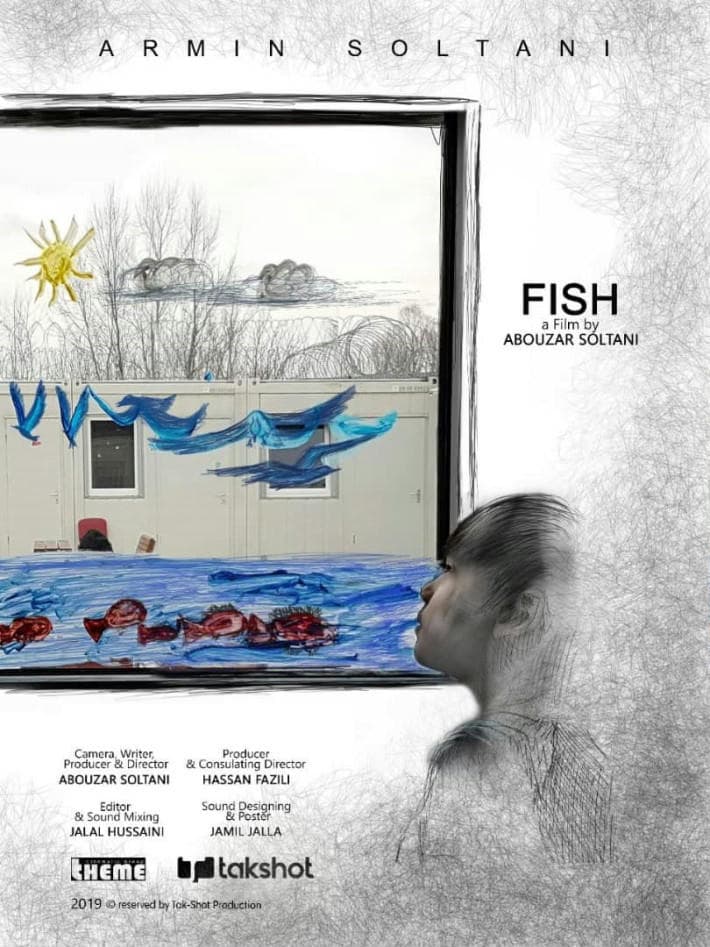

Abouzar became more and more apathetic, overwhelmed by the monotonous life and forced inaction in Röszke. Even worse, his otherwise lively, always-ready-to-play little son fell deep into depression. There was no formal education and it was not possible to play. Seeing that the vast majority of the ‘people’ in the transit zones were children, he could have had lots of playmates. However, there was nothing to do in the bleak yard in the fall and winter. Time passed at a snail’s pace. The only activities that remained were drawing on the mobile phone, sleep… and dreams. That’s when Armin’s father came up with the idea of shooting a movie with his son about his son’s dreams. The film, made with a mobile phone called ‘Fish’, was later shown in several places, but the authorities did not even temporarily release Abouzar and Armin to showcase their film at festivals.

In fact, albeit slowly, a lot happened in the Hungarian and international courts. An important development was when one of the Szeged courts temporarily banned the deportation of the Soltanis to Iran until a judgement was handed down in one of their lawsuits. The court examined whether their expulsion to Iran was at all lawful without examining their asylum application. In another action brought by the Soltanis, the same court also examined whether placement in a transit zone constituted detention. The government impossibly claimed that it was not.

Our first common victory

The Soltanis, represented by the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, won two lawsuits at the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in 2020. The victories nudged their seemingly stranded asylum application back into motion. On 19 March, the CJEU ruled that the Hungarian State was in breach of EU law by automatically rejecting all refugee applications from Serbia without examination, on the grounds that Serbia was a ‘safe transit country’ for the persecuted.

The other perhaps even more significant judgement of 14 May 2020, which in addition to the Soltanis involved two Afghan asylum-seekers, was handed down directly by EU judges. Going further than the previous decision, it even stated that asylum-seekers’ subsequent applications could not be automatically rejected on the grounds of inadmissibility if they had not been first dealt with on the merits because the applicants came through Serbia, a transit country considered to be ‘safe’. In addition, the judgement ruled that placement in a transit zone for more than four weeks constituted unlawful detention and also was in breach of EU law.

One week later, on 21 May 2020, the government closed the transit zones.

The Soltanis – if not completely, and not immediately, were finally released after 553 days. One can imagine the euphoria with which they and 300 others, mostly children, welcomed their release after a long and unjust detention. It was then that Abouzar Soltani felt a confirmation for the first time that it was worth fighting for.

Father and son were first moved to Balassagyarmat, and then to Vámosszabadi. They did not enjoy complete freedom of movement in either of the places. However, they were able to leave the closed camps at least for certain periods, and their isolation finally ended.

In the meantime, of those released from the transit zones, only they remain in Hungary. The government has not been particularly helpful or shown any sense of guilt. The family has been living in Győr for some time with the support of the charity Hungarian Baptist Aid.

Why did they stay here when the other families unlawfully detained in the transit zone were welcomed everywhere in the West? Despite all the torment and bitterness, father and son loved this country and found friends. Once they had set off on it, they wanted to walk the legal path here. And Abouzar sees an outright divine ordinance in finding a new home with his son here.

Why did they have to wait 15 months after their release to receive protection?

The delay certainly did not depend on them and their lawyer. Applying the rulings of the EU Court of Justice, the Budapest Regional Court ordered the authority to initiate a new asylum procedure as early as July 2020. But the authorities repeatedly rejected their request and kept referring to Serbia being a safe country for them.

It was another embarrassing moment when two and a half years after the Soltanis arrived here, the Directorate-General of Aliens Policing (OIF) decided to genetically examined Abouzar’s paternity. Yet until then, no one had ever doubted that he might not be Armin’s father. He proved his paternity many times not only with documents but also with his loving care. Thanks to the zeal of the Hungarian authorities, he now has a paper attesting to his biologic fatherhood.

Fortunately, the Soltanis are no longer alone since 2019. Thanks to the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, the Verzió Film Festival, church workers and helpful civilians in the transit zone, their film and a BBC report, more and more people have gotten to know and love them. Many had already crossed their fingers for them during their detention in Röszke. These days, they are even featured in a theatrical performance.

Numerous letters of support have been sent to the OIF, including from church organisations. Moreover, even Azbej Tristan, Deputy Prime Minister of the Prime Minister’s Office for Assisting Persecuted Christians and Implementing the Hungary Helps Programme, had the courage to twice issue an expert opinion in 2020 that ‘Persecution of Christians may exist in someone’s country of origin’, and this justifies the granting of refugee status. Furthermore, this opinion is binding on the authorities.

What’s next?

One might think that after that, the OIF could not have decided otherwise than to grant protection on 11 August and to announce its decision on the 18th of August. However, this was not the case. Unfortunately, given the history, there was fear that the positive substantive decision might be dragged on even further and another court round might have to take place. In the end, they did the right thing.

What will happen next to Armin and Abouzar Soltani, this likeable family? How much do they suffer from what happened to them? Without any integration assistance by the government (because it has not been for provided to refugees for years), will they be able to set down roots here? We do not know that yet. Many thanks, however, to all those who have already helped them, and also to those who continue to stand by them. Right now, we remain silent about the directors and extras in the hellish play filmed in the transit zone, because we are happy that Hungary has finally officially accepted Armin and Abouzar.

Armin’s dream is to be a member of the Hungarian national football team. We are rooting for him.